Virtual drums and guitar processors are certainly capable of delivering great sounds — but they don't always behave as you'd expect when it comes to mixdown.

When a track is hard to mix, the reason can usually be found further up the production chain. Perhaps the song isn't very good, or the arrangement hasn't been well thought-out. Sometimes the playing and singing aren't up to scratch, or poor recording has let the side down. As long as these fundamentals are sound, though, you'd expect to be able to push up the faders and get a rough balance that works. Mixing then becomes the process of refining this initial balance into something more polished.

On the face of it, then, Andy Zuk's anthemic indie-rock track 'Thought Experiment' shouldn't have been hard to mix. Not only is it a fine song, but Andy had really considered the arrangement, augmenting the basic guitar, bass and drum tracks with some very effective electronic elements. He has an excellent voice that suits his material perfectly, and as he'd used high-quality drum samples and guitar amp modelling throughout, there were no obvious quality issues with the recording. Yet Andy struggled to mix the song — and so did I.

Mixed This Month

Andy Zuk is a musician, songwriter and producer, originally from Barnsley but living in Berkshire. Having developed his musical skills while playing lead guitar for Indie band Ghosts (1998-2005), he moved on to explore a more electronic palette as half of instrumental hip-hop duo Ambulance Chasers. Now focused on releasing his own material, Andy's first full-length album The Horizon Slips combines alternative rock with electronic influences.

Keep Your Shape

When Andy sent over the multitracks, a few minor issues were apparent — the vocal was a bit thin and roomy, and the guitars perhaps a little too overdriven — but there was nothing to set the alarm bells ringing. Yet it proved mysteriously impossible to get a workable rough balance. No matter where I positioned the faders, every instrument was either inaudible or too loud, and the track as a whole just refused to gel. After an hour or two of head-scratching, I could relate to Andy's frustration, but I was nowhere near even matching his mix, let alone improving on it!

Andy's own mix definitely had good qualities, in particular its loud and proud presentation of the lead vocal with very appropriate reverb and delay effects. However, it all felt a bit over-processed (as is often the case when a struggle has taken place in the mix room) and the overall tonality felt a bit off-kilter, with too much low bass.

It took a lot of thought, and plenty of trial and error, to overcome this frustration and untangle the reasons why 'Thought Experiment' refused to be mixed. I won't describe all the dead ends and false starts that I followed along the way, but one point is crucial. When you're going through a challenging project over and over again, trying to understand what's going on, familiarity is the enemy. Repeated listening can make you accustomed to almost any mix balance, and it becomes increasingly hard to figure out if the adjustments you're making are actually improving the bigger picture, or whether you're just getting used to hearing it a certain way. It's all too easy to get sucked into focusing on details because you've become inured to more basic problems with the mix.

Retaining the right focus in these circumstances boils down to self-discipline and good mixing habits. Force yourself to take regular breaks. Switch monitoring systems for a different perspective, and listen in mono, ideally on a single speaker. And, most importantly, find some appropriate references and use them properly. It's particularly vital to make sure your references are accurately level-matched to the track you're mixing, because this is the foundation of all the comparisons you'll be making. You can often fool yourself into thinking that a reference track has more low end or a brighter guitar sound than yours, when in reality the whole track is just a couple of dB louder.

Disciplined mixing also means being ruthlessly honest with yourself. You may have established ways of processing drums or vocals that have worked on every other mix you've done. You may simply have poured hours and hours into pursuing a potential solution to a problem. But, painful though it is, you still need to be prepared to admit that it's not working, tear it all down and start again.

Not Quite Like The Real Thing

In the final analysis, the issues that made 'Thought Experiment' hard to mix mostly stemmed from the use of sampled drums and modelled guitar amps, but they were often quite subtle, especially when parts were auditioned in isolation. For example, modern drum libraries are capable of stunning realism, so when sampled drums fall short of the real thing, it's usually the programming that is the problem, but that wasn't the case here. Andy's parts were nicely done, avoiding lazy mechanical repetition at one extreme and fussy overplaying at the other. Heard in isolation, the drums sounded both well balanced and plausibly human. Yet in the mix, they either disappeared or dominated, and it was hard to make them drive the track forward.

In a typical rock arrangement, alarm bells should probably start ringing if mix compression is being triggered primarily by something other than the kick or snare drums.

After a lot of puzzlement, I eventually identified two problems. One was that while these drums were a decent approximation of a well-recorded acoustic drum kit, the drum kit they were approximating wasn't right for the song. The other was that although the virtual drum instrument had spat out files that looked like the typical components of a drum multitrack (kick drum, snare top and bottom, toms, overheads, room mics and so on), these didn't respond or behave in the mix like their counterparts in a real drum recording would.

The kit as a whole felt as though it would have been better suited to a modern metal production than to an anthemic indie guitar track. The kick drum, in particular, was incredibly scooped, with a sharp clicky attack and a colossal sub-bass 'whump', and no mid-range content at all. It certainly cut through, but it didn't sound as though it belonged to the rest of the production, and all that low-end weight seemed to drag the tempo down. I suspect that starting with this kick drum had led to some of the tonal balance problems with the original mix. To make matters worse, the amount of sub-bass seemed quite variable between individual hits. No matter how much I compressed the kick drum, some hits poked out of the mix and others got lost. The snare, meanwhile, was somewhat gutless and rattly.

Had this been a real drum recording, I might have been able to rely mainly on the overheads to produce the overall picture of the drum kit, with the close mics contributing a bit of extra punch and snap. But this wasn't a real drum recording, and the overheads did not present an overall picture of the drum kit: they were basically cymbal mics, with vanishingly low levels of snare and kick drum. In short, what the drum instrument had produced was only superficially like a conventional drum multitrack and, as far as the mix was concerned, it behaved more like a bunch of independent kit pieces arbitrarily grouped together. You might think this would work to the mix engineer's advantage but that really isn't the case. Any gain that comes from the complete elimination of spill is more than offset by the unnatural, lifeless quality that it introduces, and by the fact that the drum kit no longer sounds like a single instrument.

Short of hiring a real drummer, the best solution might have been to ask Andy for the MIDI files, and rebuild the drum tracks using different samples and mix settings. However, that would have taken this article beyond the scope of a mix 'rescue' and made it less relevant to real-world scenarios. When you're being paid to mix someone else's recordings, you'd want to think carefully before questioning this sort of production decision, for fear of overstepping the boundaries of the mix engineer's role.

Kicking Up

When I'm mixing a real drum kit recording, I usually end up doing a lot of relatively subtle processing to the individual tracks. I'll often use an expander to clean up the close mics a little; I'll experiment with polarity and phase alignment; I'll roll off unwanted low end and judiciously add some top; and I might compress individual mics to emphasise the attack or the body of the sound. None of that was necessary or appropriate to these super-clean sampled sounds. The two main issues I faced were, firstly, how to reshape the kick drum sound to give it more mid-range punch, and secondly, how to bring the whole drum kit together so that it sounded like a single instrument being played with some attitude.

One of the reasons this song was hard to mix was that the kick drum sound was extremely 'scooped', with tons of sub-bass and high-end click and nothing in between. A combination of resonant filtering and dynamic EQ helped to reshape it into something more appropriate to an indie-rock track.

One of the reasons this song was hard to mix was that the kick drum sound was extremely 'scooped', with tons of sub-bass and high-end click and nothing in between. A combination of resonant filtering and dynamic EQ helped to reshape it into something more appropriate to an indie-rock track.  I tried various ways of tackling the first problem, and the solution I eventually came up with involved a resonant high-pass filter in SoundToys' Filter Freak. By setting the cutoff to 68Hz and dialling in a fair amount of resonance, I was able to shift the sub-bass energy in the raw sound a bit further up the frequency spectrum. Adding some saturation using the same plug-in's Fat algorithm helped thicken up the mid-range, and a single band of dynamic EQ in FabFilter's Pro‑MB went some way towards evening out the variations in low-frequency content between individual drum hits.

I tried various ways of tackling the first problem, and the solution I eventually came up with involved a resonant high-pass filter in SoundToys' Filter Freak. By setting the cutoff to 68Hz and dialling in a fair amount of resonance, I was able to shift the sub-bass energy in the raw sound a bit further up the frequency spectrum. Adding some saturation using the same plug-in's Fat algorithm helped thicken up the mid-range, and a single band of dynamic EQ in FabFilter's Pro‑MB went some way towards evening out the variations in low-frequency content between individual drum hits.

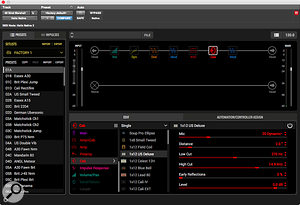

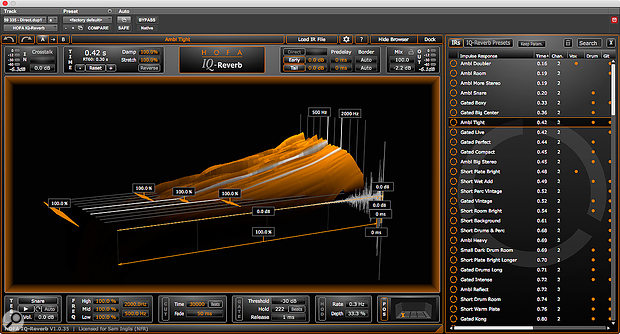

As for the second, I thought that the answer would either be to compress the drum bus in order to 'glue' everything together, or to feed the entire drum mix into a short reverb to make it sound as though everything was going on in a single space. In the event, global reverb on the drum bus sounded a bit over the top, so I used a short ambience patch as a send effect — but I sent to this not only from the snare mic, but also the kick drum and overhead tracks. To fatten up the snare, I also applied plenty of a short, fat drum room from EastWest's Quantum Leap Spaces II. And after much experimentation with different compressors, I eventually decided to process the mix bus rather than the drum submix, as I'll explain later.

Caught By The Fuzz

The raw vocal tone was rather light and a bit sibilant. Another instance of Fabfilter's Pro‑MB helped add mid-range weight and de-emphasise the top end.The other core elements of the track were a single lead vocal, plus rhythm, lead and bass guitars. The vocal obviously hadn't been tracked in a dead booth, and had a noticeable resonance around 500Hz. However, this was easily tackled using a dynamic EQ, and the general roominess wasn't problematic: Andy's own mix had made a good case for using plenty of artificial reverb and delay on his vocal, and this amply disguised the room sound. I was less keen on the actual vocal tone, which was rather bright and lacked weight in the mid-range. So, after running the vocal through a high-pass filter and the classic 'fast and slow' compression combo of an 1176 and LA‑2A emulation in series, I added another instance of FabFilter's Pro‑MB. This was set to add 3dB between 400Hz and 1.6kHz, and take out up to 6dB above 3.5kHz or so in the louder passages.

The raw vocal tone was rather light and a bit sibilant. Another instance of Fabfilter's Pro‑MB helped add mid-range weight and de-emphasise the top end.The other core elements of the track were a single lead vocal, plus rhythm, lead and bass guitars. The vocal obviously hadn't been tracked in a dead booth, and had a noticeable resonance around 500Hz. However, this was easily tackled using a dynamic EQ, and the general roominess wasn't problematic: Andy's own mix had made a good case for using plenty of artificial reverb and delay on his vocal, and this amply disguised the room sound. I was less keen on the actual vocal tone, which was rather bright and lacked weight in the mid-range. So, after running the vocal through a high-pass filter and the classic 'fast and slow' compression combo of an 1176 and LA‑2A emulation in series, I added another instance of FabFilter's Pro‑MB. This was set to add 3dB between 400Hz and 1.6kHz, and take out up to 6dB above 3.5kHz or so in the louder passages.

The guitars were harder to deal with. Like the drums, the rhythm guitar and bass guitar sounded fine in isolation, but they either vanished in the mix or sat on top of it. The lead guitar, meanwhile, was very harsh, with a lot of top-end fizz that came and went abruptly.

The guitars were harder to deal with. Like the drums, the rhythm guitar and bass guitar sounded fine in isolation, but they either vanished in the mix or sat on top of it. The lead guitar, meanwhile, was very harsh, with a lot of top-end fizz that came and went abruptly.

I decided fairly quickly that too much saturation had robbed the rhythm and bass sounds of their definition. As Andy had sent over the raw DI'd tracks as well as the processed tracks, I hoped to use amp simulators to come up with something that still felt powerful, but didn't dissolve into a featureless wall of fuzz. This turned out to be a lot harder than I expected, because the rhythm guitar part had been pretty forcefully strummed, and seemed too dynamic for all of the amp simulators I tried. When I adjusted the controls to give a classic AC30 or Marshall rhythm tone with a bit of crunch to it, note attacks got brittle and nasty. In the end, I resorted to putting a clean compressor with a very fast attack and release ahead of the amp simulator.

The raw lead guitar sound was brutally harsh and quite variable from one moment to the next. Oeksound's invaluable Soothe plug-in helped save the day, along with a cabinet emulation in Line 6's Helix Native.This worked but it didn't address the other main issue, which was that the rhythm and lead guitars kept fighting for the same space in the mix. Ordinarily, you'd deal with this by trying to make the two sounds complementary so that, for instance, a very mid-focused lead sound sits on top of a slightly scooped rhythm sound. In this case it was hard to give the lead sound any sort of focus at all, because it was so inconsistent. The part itself moved around the fretboard a lot, and it seemed to have been played through both an aggressive fuzz and a pitch-shifter, resulting in calmer moments being punctuated by squealing glissandos and blasts of piercing fizz. Rather than working together, the two guitar parts alternately stamped on each other.

The raw lead guitar sound was brutally harsh and quite variable from one moment to the next. Oeksound's invaluable Soothe plug-in helped save the day, along with a cabinet emulation in Line 6's Helix Native.This worked but it didn't address the other main issue, which was that the rhythm and lead guitars kept fighting for the same space in the mix. Ordinarily, you'd deal with this by trying to make the two sounds complementary so that, for instance, a very mid-focused lead sound sits on top of a slightly scooped rhythm sound. In this case it was hard to give the lead sound any sort of focus at all, because it was so inconsistent. The part itself moved around the fretboard a lot, and it seemed to have been played through both an aggressive fuzz and a pitch-shifter, resulting in calmer moments being punctuated by squealing glissandos and blasts of piercing fizz. Rather than working together, the two guitar parts alternately stamped on each other.

I couldn't easily generate a new version from the lead guitar DI track, because this didn't have the pitch-shifting effect baked in. In any case, the fuzz was obviously an artistic decision on Andy's part, and a valid one in principle. The challenge was to lose the harshness and make things more consistent, without robbing the part of its undeniable character. I probably tried 10 or more different ways of doing this, and in the end, I settled on a combination of Oeksound's life-saving Soothe plug-in and a cabinet emulation in the Line 6 Helix Native amp simulator.

I couldn't easily generate a new version from the lead guitar DI track, because this didn't have the pitch-shifting effect baked in. In any case, the fuzz was obviously an artistic decision on Andy's part, and a valid one in principle. The challenge was to lose the harshness and make things more consistent, without robbing the part of its undeniable character. I probably tried 10 or more different ways of doing this, and in the end, I settled on a combination of Oeksound's life-saving Soothe plug-in and a cabinet emulation in the Line 6 Helix Native amp simulator.

The fizz and fuzz were now somewhat under control, and it was possible to distinguish the lead guitar from the rhythm guitar at least some of the time. By applying high-pass filters to the guitar parts and layering the original distorted bass with a cleaner version, I was also able to make the bass part sit at a comfortable level. This left one further problem: with the vocal, lead, rhythm and bass parts all panned centrally, the only thing that had any stereo width was the drum kit — which, in typical sampled drum style, was unnaturally wide.

The DI'd rhythm guitar was too spiky for all the amp simulators I tried, so I ran it through a compressor first. A duplicate was also fed through a short reverb set 100 percent wet and opposite panned to create a stereo effect.

The DI'd rhythm guitar was too spiky for all the amp simulators I tried, so I ran it through a compressor first. A duplicate was also fed through a short reverb set 100 percent wet and opposite panned to create a stereo effect.

This wouldn't have been a problem if the rhythm guitars had been double-tracked, since the two parts could then have been hard-panned to make space in the centre. In the past, I've quite often created an artificial double-track by duplicating the original part and editing it, but this is only possible when every musical section is repeated at least once, which wasn't the case here. Other tricks, such as using stereo imaging plug-ins or applying a very short delay to one side, can be risky when you're applying them to such an important musical part, because they can have serious consequences when the mix is heard in mono. I tried using different amp simulator settings on the left and right sides, but this alone didn't create enough sense of width, so in the end I fed the right-side part through a very short reverb set 100 percent wet before the amp simulator. Like a short delay, this had the effect of distancing the duplicate from the original, but it seemed much more mono-compatible.

The Master Game

Although the complete Pro Tools mix session for 'Thought Experiment' was quite large, many of the tracks only played in short sections of the song, and 90 percent of the mixing work was focused on the drums, bass, guitar and vocal.Including all of my aux effect and subgroup tracks, the final mix session in Pro Tools totalled at least 60 tracks, but only three or four of these had conventional EQ on them. This is probably a consequence of introducing master bus EQ very early in the mix process. I find this often means doing less EQ'ing on individual tracks, and working with an overall mix tonality that is already in the ballpark from the start also makes it easier to make the right decisions when you do process individual tracks. Tracks with distorted electric guitars often seem particularly responsive to mix-bus EQ, and my usual starting point is a broad mid-range lift using the HMF band in Acustica Audio's Diamond Color-EQ, often coupled with some additional high-frequency air. I rarely touch the low-frequency controls, but in this case I found that an additional dip at 120Hz helped to clear out a congested lower mid-range.

Although the complete Pro Tools mix session for 'Thought Experiment' was quite large, many of the tracks only played in short sections of the song, and 90 percent of the mixing work was focused on the drums, bass, guitar and vocal.Including all of my aux effect and subgroup tracks, the final mix session in Pro Tools totalled at least 60 tracks, but only three or four of these had conventional EQ on them. This is probably a consequence of introducing master bus EQ very early in the mix process. I find this often means doing less EQ'ing on individual tracks, and working with an overall mix tonality that is already in the ballpark from the start also makes it easier to make the right decisions when you do process individual tracks. Tracks with distorted electric guitars often seem particularly responsive to mix-bus EQ, and my usual starting point is a broad mid-range lift using the HMF band in Acustica Audio's Diamond Color-EQ, often coupled with some additional high-frequency air. I rarely touch the low-frequency controls, but in this case I found that an additional dip at 120Hz helped to clear out a congested lower mid-range.

As I mentioned earlier, I also explored various approaches to dynamics processing on the drums. Sampled kits being what they are, this wasn't needed for corrective purposes, as it might be when a real drummer gets a bit carried away or has an uneven technique. It was more about trying to help the separate elements of the kit to gel, and to support the mix as a whole. After a lot of mucking about on the drum bus, I eventually decided that this was better done using dynamics processing on the master bus, where it could manipulate the way in which the drums pushed against the guitars and other elements.

Fast-acting dynamics on the master bus can help a 'spiky' drum kit gel with the rest of the track. In this case I simply drove the master limiter hard to push the kick and snare back into the mix.There are at least two basic approaches to 'mixing into' compression, and both of them rely on the kick and snare drums being the loudest things in the mix. One option is to set a relatively slow attack and a fast release. This lets each kick and snare hit punch through before the compressor clamps down, and can be helpful in situations where you want the kit to sound bigger in relation to the rest of the mix. The other approach is to start with the kick and snare slightly too loud, then set a very fast attack time, so that the compression pushes them back into the mix. This can be a valuable way of making a slightly spiky drum kit gel with other instruments that are much less dynamic, and was the approach I explored in this case. As it happened, I needed to use a brickwall limiter on the output anyway to match the level of Andy's mix, so I let this do the heavy lifting, inflicting as much as 6dB gain reduction on loud snare hits.

Fast-acting dynamics on the master bus can help a 'spiky' drum kit gel with the rest of the track. In this case I simply drove the master limiter hard to push the kick and snare back into the mix.There are at least two basic approaches to 'mixing into' compression, and both of them rely on the kick and snare drums being the loudest things in the mix. One option is to set a relatively slow attack and a fast release. This lets each kick and snare hit punch through before the compressor clamps down, and can be helpful in situations where you want the kit to sound bigger in relation to the rest of the mix. The other approach is to start with the kick and snare slightly too loud, then set a very fast attack time, so that the compression pushes them back into the mix. This can be a valuable way of making a slightly spiky drum kit gel with other instruments that are much less dynamic, and was the approach I explored in this case. As it happened, I needed to use a brickwall limiter on the output anyway to match the level of Andy's mix, so I let this do the heavy lifting, inflicting as much as 6dB gain reduction on loud snare hits.

Incidentally, listening to how your mix responds to compression can sometimes provide useful information about the balance. In a typical rock arrangement, alarm bells should probably start ringing if mix compression is being triggered primarily by something other than the kick or snare drums. I've heard several tracks lately where the bus compressor is being set off mainly by a vocal that is proud of the mix. The audible result of this is that, rather than providing a solid bedrock, the instrumental parts behind the vocal become unstable in level. I think you can hear a little bit of this in Andy's original mix of 'Thought Experiment'.

Back In The Real World

If I had to sum up the fundamental challenge here, it's that although the 'Thought Experiment' multitrack somewhat resembled a recording of a guitar band, it wasn't one, and it didn't behave like one at the mix. What it brought home to me was that when you are mixing a conventional band recording, you always have a reference point to focus on. You can envision how the band would have sounded in the studio, and work towards achieving an idealised version of that sound at the mix. That just isn't the case with a track assembled using drum samples and virtual guitar sounds: each individual part might appear fine on its own, but an overall reference point is sometimes very hard to reconstruct. Even a rough and ready live recording made with a real band would have been easier to pull together, and if Andy goes on to record more of his material, I'd definitely recommend trying to find the budget to hire a drummer and a studio to do the basic tracking. If nothing else, it's a lot more fun than tapping in beats on a MIDI keyboard!

A Question Of Scale

Andy Zuk had clearly put a lot of thought into his arrangement, and there were a number of synth and sample-based electronic parts that popped up throughout the track. These formed the main part of the arrangement in the intro and in two breakdowns, and elsewhere added a lift to the chorus and other high points.

From a mix point of view, the main issue these presented was one of scale. Like a lot of synthetic sounds, these were typically very full-range and loud, so it was easy to end up in a situation where they overwhelmed the rest of the mix and made it sound small. To make them work effectively, they needed to be reduced to the same apparent size as the other elements of the mix. This is something I usually achieve through band-limiting and saturation, and I'm particularly fond of plug-ins such as SoundToys' Decapitator and Softube's Harmonics, which let you apply different styles of saturation while simultaneously rolling off high and low end. I used both of these plug-ins on 'Thought Experiment', and I also automated various parameters within SoundToys' Filter Freak and Line 6's Echo Farm during the second breakdown, to create the impression of everything getting smaller and then bigger again!

Remix Reaction

Andy Zuk: "The difference between the original and Sam's mix really is like night and day — he's addressed all of the problems that I knew bugged me about my version, but which I didn't know how to solve. The main thing that jumps out is the clarity and separation in the rescued mix — the instrumentation has been unearthed from a fair amount of mud and distortion, and you can really hear the different elements as discernible parts now. I think I'd become overly attached to some of the more heavily overdriven bass and guitar sounds that I'd used when sketching parts out; the whole mix breathes so much better with these reamped and cleaned up."

"Of all the tracks on the album, I really struggled with the low end on this song and just couldn't get it right. The improvement here is really apparent: the bass has a tighter and more consistent low-end presence now that's really lacking in the original. And try as I might, I just couldn't get rid of the sibilance on the vocal properly, particularly in the pre-choruses. Sam's processing has made a massive improvement here, and the vocal now has a much smoother and 'hi-fi' sound, without the unpleasantly hyped top end."

"It's been a fantastic experience having Sam work on this track. The technical changes have really improved it, but it's also really inspiring to see what's possible with the same basic inputs and recordings. Thanks Sam — you've taught me a lot and have really raised the bar for my future projects!"

Listen Online

You can find a number of audio clips demonstrating the changes Sam made to this track by downloading the ZIP file of WAVs and MP3s here: